Keywords

acute coronary syndrome, pregnancy, spontaneous coronary arteries dissection, women

Abbreviation list

ACS acute coronary syndrome

CAD coronary artery disease

CMVD coronary microvascular dysfunction

MINOCA myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary arteries

SCAD spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Take-home messages

- Cardiovascular disease is the worldwide leading cause of death in women but traditional risk factors, as well as sex-related risk factors, are usually underestimated in women

- Clinical presentation of women with ACS may be atypical

- Women with ACS often experience under- or delayed diagnosis and undertreatment

- Clinical trials have recruited a low number of women

Patient-oriented messages

- Traditional risk factors, as well as gynaecology and obstetric problems could enhance women’s cardiovascular risk, it is therefore of utmost importance to treat all correctable risk factors

- Even young women could experience ACS, thus it is fundamental to seek medical attention soon in case of symptoms, including atypical ones

- Cardiac medicines and procedures are as important in females as in males, so careful adherence to cardiologic prescription is of paramount importance

Impact on practice statement

Every physician taking care of a female patient should know that ischaemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in women. It is therefore important to understand how to select patients at risk of cardiovascular events, rapidly intervene in case of ACS, and recommend adequate secondary prevention treatment.

Key messages in this article include

- Controlling traditional risk factors, focusing particularly on smoking, diabetes, and obesity

- Giving more attention to women who have experienced gynaecological diseases or complicated pregnancies, as these represent non-traditional cardiac risk factors.

- Overcoming physician selection bias when assessing female patients reporting chest pain.

- Keeping in mind that the female way of reporting symptoms can be misleading.

- Considering the uniqueness of the pathophysiology of ACS in women.

- Recommending invasive procedures and evidence-based therapies, even if women look frailer and are more prone to haemorrhagic complications.

Introduction

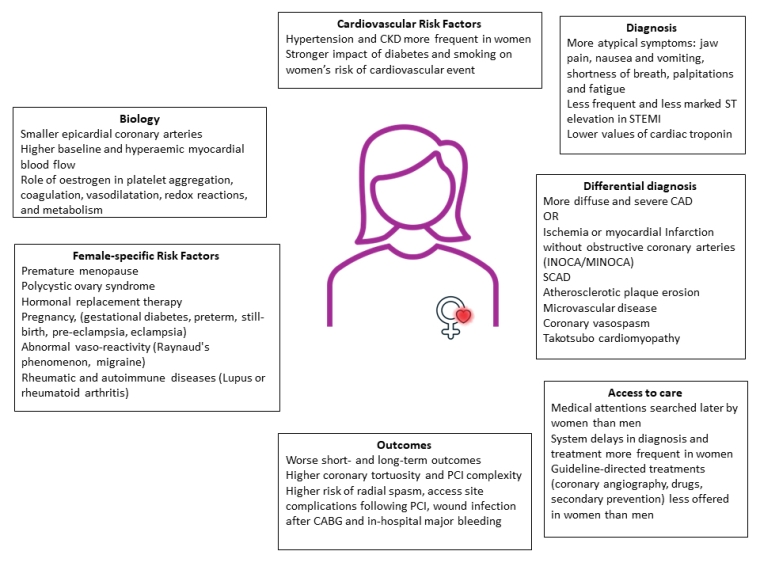

Acute coronary syndrome is an umbrella term for myocardial ischaemia, resulting from diseases of the coronary circulation. Traditionally misconceived as a man’s disease, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women all over the world[1]. Although there has been dramatic progress in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease, age-standardised mortality rates for cardiovascular disease declined from 1990 to 2021 by 47% in males but only 42% in females [2]. The disparity in mortality between men and women may be the consequence of a combination of factors, such as delayed presentation, misinterpretation of symptoms, underdiagnosis, and undertreatment, as well as different pathophysiologies, with specific risk factors, patterns of symptom presentation, laboratory findings, and imaging results (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Women and cardiovascular disease.

*The logo on the silhouette of the woman in the centre of this is the logo of the CardioDonna Project. CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CKD: chronic kidney disease; FFR: fractional flow reserve; INOCA: ischemia without obstructive coronary arteries; MINOCA: myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary arteries; PCI percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG coronary artery bypass grafting; INOCA ischemia without obstructive coronary arteries; MINOCA myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary arteries; SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

Traditional risk factors and female sex-related risk factors

As symptoms are often atypical in women with ACS, a comprehensive preliminary assessment of the woman with suspected ACS is of fundamental importance. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors remain a significant problem in women who, in recent years, have had a worsening of their risk factor profile. For instance, nowadays nearly a third of women worldwide are obese [3]. Furthermore, diabetes confers a higher cardiovascular risk in women, than in men (4-fold vs 2.5-fold) [4]. Even if the smoking prevalence is lower in females, smoking has a stronger impact on women’s risk of cardiovascular events (3.3- vs 1.9-fold) [5]. Finally, as male sex is a cardiovascular risk factor per se, women at high-risk have long been forgotten. It should be noted that women have some notable differences in cardiac biology as well. In females, the epicardial coronary arteries are smaller, even after accounting for body habitus and left ventricular (LV) mass, while baseline and hyperaemic myocardial blood flow are higher [6]. This increases endothelial shear stress which is ultimately protective against the development of coronary artery disease (CAD), particularly at a younger age.

Sex hormones have wide-ranging effects throughout the circulatory system. Oestrogens inhibit platelet aggregation, decrease plasma levels of procoagulant factors (like the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1), and stimulate the production of prostacyclin and nitric oxide, thus resulting in potent antiplatelet effects. They also positively affect the cholesterol profile by increasing high-density lipoproteins. Oestrogens reduce mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species, enhancing the antioxidant defence mechanism. Overall, these varied actions of endogenous oestrogens appear to be cardioprotective, lowering the cardiovascular risk profile in pre-menopausal women. Consequently, oestrogen withdrawal after menopause has many negative effects, including endothelial dysfunction, an alteration in body fat distribution, higher insulin resistance, and increased sympathetic nerve activity [6]. Interestingly, replacing oestrogen after menopause has not shown any beneficial effects, and both the arterial and venous cardiovascular risk continue to increase. The effects of plasma progesterone levels on platelet function are less well known. Hormonal perturbations, like polycystic ovary syndrome, hysterectomy, premature menopause, replacement or contraceptive therapy, might account for non-traditional cardiac risk factors unique to women. Complications during pregnancy, such as pregnancy-related hypertension, gestational diabetes, preterm and still-birth have all been associated with increased cardiovascular risk, while pre-eclampsia confers the highest increase of future cardiovascular disease (1.5-2.7-fold) [7]. Breast cancer therapy also confers a high cardiovascular risk, both for overlapping risk factors and the detrimental effect of the treatment. However, although some of these variables have been mentioned in recent guidelines [6], these risk factors have yet to be studied or included in the most frequently applied cardiovascular risk calculators. In addition, women are more likely to suffer from disorders relating to abnormal vasoreactivity, including Raynaud's phenomenon and migraine, and from autoimmune diseases like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, which have been proven to double the cardiovascular risk [7].

Pathophysiology of ACS in women

The pathophysiology of ACS may also differ by sex. Women have more diffuse and non-obstructive CAD, with a reduced plaque burden and calcium content. Notably, up to one-third of women experience myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). This could be due to the erosion of a non-significant plaque, which is the most frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in women, while plaque rupture is more frequent in men [8]. Other causes of ACS are myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, coronary vasospasm, ischaemia without obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), or spontaneous coronary artery dissections (SCAD).

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy accounts for about 3% of all ACS cases and 80% of patients are postmenopausal women who have had an emotional trigger [6]. While 95% of patients present following negative emotional stress such as the death of a relative, fear, or anger, positive emotions can also modulate the autonomic nervous system response in a similar way. It is known that sympathetic nervous activity increases with age and even more so in the female sex.

Coronary vasospasm is caused by the vasoconstriction of coronary arteries, most often at rest and during nighttime, or early in the morning. Although it is more prevalent in the male population, coronary vasospasm can occur in women as well.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMVD) is defined in presence of angina or abnormal non-invasive functional tests and absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (<50% coronary diameter reduction and/or fractional flow reserve >0.80) at coronary angiography. This condition is twice as prevalent in women than men and is associated with impaired outcomes. The causes can be structural (atherosclerotic microembolisation, hypertrophy-induced perivascular compression, capillary rarefaction) or functional, with enhanced microvascular constriction or attenuated dilatation due to an impaired endothelium releasing vasoactive substances. It is therefore crucial to undergo a specific diagnostic work-up, either with non-invasive techniques (positron emission tomography, perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance or echocardiographic measurement of coronary flow reserve), or invasive diagnostic modalities (coronary flow reserve with adenosine and invasive vasoreactivity testing, with administration of acetylcholine or ergonovine).

SCAD is an infrequent cause of ACS in the general population, but it accounts for a significant proportion of ACS cases in young/middle-aged women, as up to 90% of SCAD patients are women [9]. During SCAD, an acute separation of the coronary arterial layers (intima and media) happens, followed by the development of an intramural haematoma and this compromises coronary blood flow (an example is provided in Video 1). The risk factors for SCAD can include hormonal therapy, hypothyroidism, fibromuscular dysplasia, inflammatory or connective tissue disorders. Chest pain in SCAD patients is even more common than in atherosclerotic ACS patients, maybe because dissection per se is inherently painful. Young women traditionally fall into a low-risk category based on traditional risk factors, therefore, a high index of suspicion should be maintained to avoid missed diagnoses. Coronary angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of SCAD, and in case of diagnostic uncertainty, intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography can be carefully considered. Conservative management is generally recommended, because of spontaneous dissection healing and a high percentage of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) complications. PCI, however, must be considered when coronary flow is impaired and recurrent ongoing ischaemia or haemodynamic instability is present, or there is a large area of myocardium at risk. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is recommended if PCI is not feasible or unsuccessful, but a significant rate of graft occlusion at 5 years (68%) is reported [1]. Medical therapy includes beta-blockers and stringent blood pressure control. Recurrences, usually presenting in a new vessel, are frequent among SCAD patients, occurring in up to 29% at 10 years [9]. Among SCAD patients, those with pregnancy-related SCAD have the worst prognosis. Pregnancy is known to increase the risk of acute myocardial infarction (3 to 4-fold compared with age-matched nonpregnant women) [10]. As maternal age increases, traditional risk factors for coronary artery disease become more and more important. In addition, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, fluctuating oestrogen/progesterone levels, and peripartum drugs, such as tocolytics and oxytocin, can enhance vascular reactivity. On the other hand, labour is a haemodynamically stressful time and can increase coronary shear stress. Lastly, the known hypercoagulability state during pregnancy can provoke an ACS, including ACS due to paradoxical embolisation. Most cases of ACS in pregnancy are due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection (43%), most commonly during the third trimester or post-partum. Although ACS in pregnancy is a rare event, it carries about a 7% risk of maternal and foetal mortality [10]. Management of ACS is naturally complicated by the need to avoid foetal damage, and any radiation dose must be minimised, as much as possible. However, this should not prevent primary PCI, as the dose of ionising radiation needed is far below the level of foetal damage. A radial approach should be preferred, and uterus shields should be used.

Video 1. An example of SCAD with intramural haematoma and impaired blood flow involving the mid circumflex artery and two marginal branches in a 50-year-old woman.

Current guidelines recommend aspirin, heparin, and clopidogrel, which should be used solely when strictly necessary and for the shortest duration possible. The use of glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors, bivalirudin, prasugrel, and ticagrelor is not recommended due to the lack of data on pregnant women. Other drugs traditionally used, like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and statins, are contraindicated. While beta-blockade may be beneficial, potential side effects including neonatal bradycardia and intrauterine growth retardation should be considered. Delivery should be ideally postponed for at least 2 weeks post-ACS.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Chest pain is the most common clinical presentation of ACS. However, up to a quarter of women are more likely to present without chest pain, while reporting atypical symptoms, like jaw pain, nausea and vomiting, shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue. Women are less likely to present with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and any ST-elevation is usually less marked than in men [11]. For diagnosis of STEMI, the entity of ST elevation in V2–V3 is less in women regardless of age than in men (≥1.5 mm vs ≥2.5 mm in men <40 years, ≥2 mm in men ≥40 years) [1].

Myocardial infarction can be diagnosed with a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers, in a clinical context of acute myocardial ischaemia. Significantly lower values of cardiac troponin are observed in women as compared with men [3]; therefore, high sensitivity troponin assays have different sex-specific cutoffs to improve diagnostic and prognostic information [3]. As troponin levels tend to increase with age, women reach equivalent cardiac troponin concentrations approximately a decade after men.

Risk stratification schemes, like Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE), Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk scores, and Killip classification are derived from a predominantly male population, and there is still a debate about their ability to accurately risk stratify ACS women patients.

Therapy and outcomes

Although current guidelines recommend immediate or early coronary angiography in all ACS patients, women are less likely to undergo invasive coronary angiography than men. When performed, it usually reveals more diffuse and critical CAD than found in men. In addition, women who undergo PCI are less frequently treated with a transradial approach and tend to have more access-site complications [12]. Tortuosity and small vessel calibre may add complexity to the procedure. Antiplatelet drugs play a key role in the acute phase of treatment for ACS. However, the efficacy and safety of these drugs may differ between genders, as women have lower body weight, higher fat/water balance, lower clearance, and different hormonal composition, which can ultimately affect pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Compared to men, young women have greater baseline clotting tendency, with greater residual platelet reactivity while on both aspirin and clopidogrel. Although the underlying mechanism of this sex difference is not completely understood, it is supposed that high levels of oestrogens lead to increased platelet aggregation and platelet adhesion to fibrinogens. Cangrelor, a relatively new, potent intravenous inhibitor of the P2Y12 receptor, has been demonstrated to be as effective at the time of PCI in women as in men [13]. Fondaparinux has been shown to reduce major cardiac events (MACE) in a similar way in men and women, while showing a trend to reduced major bleeding in female gender [14]. Taken together, these data indicate that sex should not influence patient selection for the administration of P2Y12 inhibitors; however, special attention must be paid to women in properly applying weight-, renal- and age-adjustments of anti-thrombotic agents, such as prasugrel, heparins, and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors.

Several studies have suggested that women have worse outcomes than men after an ACS. The underlying causes could be the women’s older age and a greater prevalence of comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, obesity, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease, as compared to age-matched men. This higher comorbidity burden could have led to the decreased likelihood of angiography or evidence-based care. Women with STEMI have a 7% lower probability of receiving angiography and a 21% lower probability of receiving revascularisation. Notably, no improvement in this sex-related treatment gap was observed between 1995 and 2014 [15].

Regarding medical therapy, women with ACS have a 17% lower probability of receiving non-aspirin antiplatelets, as compared to men, and, when prescribed, the low-intensity P2Y12 inhibitor clopidogrel was more frequently used [15], perhaps because females have more than 2-fold in-hospital major bleeding events compared to their male counterparts [16]. Moreover, women are less likely to receive medications for secondary prevention, having a 4% lower probability of receiving betablockers, 5% for ACE inhibitors, and 13% for lipid-lowering medications. A possible explanation could be that the angiographic absence of coronary artery disease leads the treating physician to omit evidence-based medication [15]. Furthermore, recent reports have shown that women discontinue lipid-lowering medication more frequently than men by 13% [15]. Additionally, women have a more adverse sociodemographic and psychosocial profile, including lower income and limited formal education, with possible misinterpretation of symptoms and underestimation of their own cardiovascular risk. Women often experience high family stress levels, and many competing and conflicting priorities, factors that can ultimately lead to delays in presentation. Moreover, higher levels of depression and perceived stress may influence recovery and prognosis. Finally, it is well known that women have been inadequately studied in cardiovascular research. Scientific societies are now trying to increase the participation of women in clinical trials, to ensure that treatment recommendations meet their specific health needs.

The Mauriziano CardioDonna Project

Since young women are the most neglected with regards to cardiovascular prevention and care, at Mauriziano Hospital we have created a dedicated care path for women of childbearing age (30-50 years old). As far as we know, this centre is unique in all the world because women are offered care from a entirely female-led team starting from prevention (including nutritional care) to invasive treatment when needed. The project started on 29 May 2023. So far, we have enrolled 48 patients aged 43±6 years old. Smoking, hypertension, family history per CAD, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and autoimmune diseases were present in 25%, 15%, 12.5%, 4%, 42%, and 21%, respectively. The majority (62%) had a previous pregnancy, the overall rate of prior complicated pregnancies was 17% (8 patients). Early menopause was experienced in 13%. We found a diagnosis of cardiac disease in 17%. With specific regards to CAD/ACS: one patient had a previous SCAD, and another underwent coronary angiography due to the finding of an ejection fraction of 25% and New York Heart Assocation Functional Class III-IV. Three-vessel disease was found and it was treated percutaneously since heart surgeons refused to proceed due to the complex anatomy. Our experience shows a high incidence of cardiovascular risk factors in a subgroup of very young women highlighting the need to do more for these patients.

Conclusions

Cardiovascular disease in women is an increasingly recognised clinical problem. Despite several efforts aimed at reducing discrepancies in healthcare over past decades, inequalities between the genders are still present in substantial measure. Future research will have to overcome barriers accounting for the low numbers of women enrolled in trials and to explore sex and gender differences in biology. Focusing attention, spreading knowledge and creating dedicated ambulatory services may help clinicians to mind the gap.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.