Take-home messages

- Engaging and educating the patient is a key component of ACS care and should take place throughout the patient journey, from admission to hospital discharge and cardiac rehabilitation.

- Patients discharged after ACS should be directed to care pathways appropriate to their individual risk level in order to ensure appropriate patient management.

- Healthy behaviours should be encouraged in the immediate post-event phase and should be given high priority. Programmes that encourage early lifestyle modification and secondary prevention should be implemented and justify a significant investment.

Introduction

Secondary prevention after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) should be offered to every patient and should start as early as possible after the index event. It has been shown to both increase quality of life and to decrease morbidity and mortality.

The optimal follow-up management is based on the following key points: patient-centred care, the number of follow-up visits, rehabilitation, lifestyle management and pharmacological treatment (see Long-term clinical management after an acute coronary syndrome). Collaborative management using the best available evidence leads to better treatment compliance, better self-care, improved health literacy, better medication adherence, decreased anxiety and depression, and fewer hospitalisations (Figure 1). Adherence to medical treatment is a priority. The effects of the adherence to behavioural recommendations and the benefit that comes from lifestyle modification is less well understood. [1]

Figure 1. Information for patients on how to optimize their ‘heart health’ after an acute coronary syndrome. With permission from Oxford University Press from [1].

BMI: body mass index; LDL: low-density lipoprotein

Patient-centred care

ACS patients should be managed with a patient-centred care approach which will improve patient outcomes and enhance their quality of life. Patients who are regarded as equal partners in their ACS medical management are more likely to actively engage and participate in their own healthcare. For this, we can use the ‘teach back’ method, in which the patient confirms that they have understood the clinical information provided by explaining the principles back to the healthcare provider (Figure 2) [1].

Figure 2. The ‘teach back’ technique. With permission from Oxford University Press from [1].

When teaching patients, it is important to appreciate that the level of health literacy for each individual is different. Many patients have low health literacy, so it may be useful to provide information in small doses and to check for understanding after each element is provided. Actively involving family and friends (in accordance with the patient’s wishes) in the care process means their contribution to patient recovery is augmented through person-centred care.

Educational material, such as information on medication, lifestyle factors, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the patient care pathway.

Engaging and educating the patient is a key component of ACS care and should take place throughout their patient journey, from admission to hospital discharge and cardiac rehabilitation.

Visits after ACS discharge

Once the ACS is stabilised (<1 year), patients should be monitored more vigilantly because they are at greater risk for complications and because they may require changes in their pharmacological treatment [2].

Thus, the 2019 ESC guidelines [3] recommend at least two visits in the first year of follow-up (Figure 3). In patients who had LV systolic dysfunction prior to revascularisation or after the ACS, a reassessment of LV function must be considered 8-12 weeks after the intervention. Cardiac function may have improved, owing to mechanisms such as recovery from myocardial stunning or hibernation which can be reversed by revascularisation [4]. Likewise, a non-invasive assessment of myocardial ischaemia may be considered after revascularisation to rule out residual ischaemia or to document the existing residual ischaemia as a reference for future assessments.

Figure 3. Proposed algorithm according to ACS patient. The frequency of follow-up may be subject to variation based on clinical judgement. Adapted with permission from Oxford University Press from [3].

Cardiovascular caregiver: internist, general practitioner, or cardiovascular nurse. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; ECG: electrocardiogram; MI: myocardial infarction

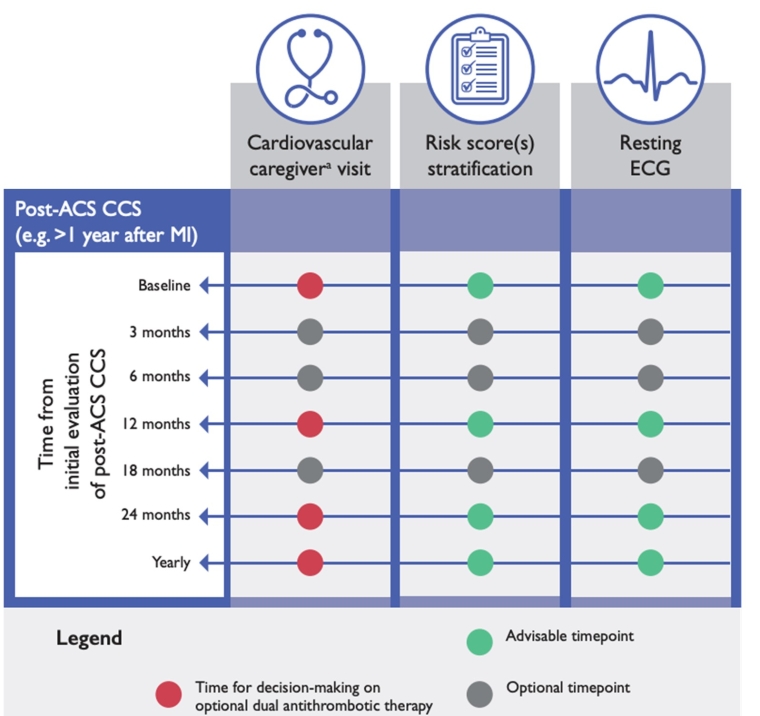

Periodic assessment of the patient’s individual risk should be considered. The 2019 ESC guidelines [2] propose an algorithm for determining when the patient should meet with their cardiovascular caregivers, as well as for the re-evaluation of risk score stratifications and resting ECG analyses. The frequency of follow-up may be subject to variation based on clinical judgement.

Cardiac rehabilitations

Cardiac rehabilitation programs (CR) are currently gaining popularity; their emphasis is on improving long-term outcomes and quality of life for patients with a history of ACS. Secondary prevention is most effectively provided through cardiac rehabilitation. CR programmes are no longer limited to the prescription of physical exercise but also include lifestyle changes, risk factor management, psychosocial care, and dynamic evaluations.

All ACS patients should participate in a comprehensive CR program, which should start as early as possible after the index ACS event [5]. CR may be performed in in-patient or outpatient settings, and take into account age, frailty, results of prognostic risk stratification, and comorbidities. In this program, the patient’s adherence to and persistence in treatment should be assessed. It is important to recognise that adherence has complex underlying psychological drivers, and therefore a whole-systems approach is mandatory.

Despite proven benefits [6], the rates of referral to, participation in, and implementation of CR programs are low [7].

Many patients adopt healthier lifestyles during CR but relapse to premorbid habits when returning to everyday life. Telerehabilitation may be an effective strategy to maintain a healthy lifestyle over time and can support or even partially replace conventional, centre-based CR. Telerehabilitation means rehabilitation from a distance, covering all CR core components, including telecoaching, social interaction, telemonitoring, and e-learning. Therefore, more research on the impact of telerehabilitation on outcomes is still needed, as are investigations into health and digital literacy in CR.

In addition to alternatives to CR, there is also a need for stronger endorsement of CR by physicians, cardiologists, and healthcare professionals [8]. It is also important to initiate and establish a strong partnership between patients and healthcare professionals as early as possible [8].

Lifestyle management

Lifestyle management is one of the cornerstones of comprehensive CR. Studies in secondary prevention settings indicate beneficial effects on prognoses [7]. Implementing healthy lifestyle behaviours decreases the risk of subsequent cardiovascular events and mortality and is an excellent and essential addition to secondary prevention therapy.

Resuming prior activities, including returning to work, engaging in personal and social activities, driving and travelling are important components of recovery after ACS. Offering adequate psychosocial and vocational support as required is an important part of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation [9].

Treating risk factors is essential [9]:

- Tobacco abstinence is associated with a reduced risk of re-infarction (30–40%) and death (35–45%) after an ACS. Measures to promote cessation of smoking are therefore a priority after an ACS.

- A healthy diet and eating habits influence cardiovascular (CV) risk. Adopting a Mediterranean-style diet can help reduce CV risk in all individuals, including persons at high CV risk and patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

- It is recommended to restrict alcohol consumption to a maximum of 100 ml per week (same limit for men and women)

- General physical activity recommendations include a combination of regular aerobic physical activity and resistance exercise throughout the week, which also forms the basis of recommendations for patients post-ACS. However, it is important to recognise that this daily physical activity does not replace participation in exercise-based CR.

- It is recommended that all patients have their mental well-being assessed using validated tools before discharge, with consideration of onward psychological referral when appropriate.

Impact on practice

Rehabilitation is the cornerstone of secondary prevention after an ACS. Patient-centred care is essential and should be provided through therapeutic education rather than just patient information.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.