Background

Congestive heart failure is one of the major health care problems in western countries. Its prevalence is increasing and, together with diabetes and atrial fibrillation, it is considered one of the three cardiovascular epidemics of the third millennium, emphasising the importance of diagnosing potentially reversible etiologies of heart failure.

Tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy (TIC) is defined as systolic and/or diastolic ventricular dysfunction resulting from a prolonged elevated heart rate which is reversible upon control of the arrhythmia or the heart rate. TIC has been reported in both experimental models and in patients with incessant or very frequent tachyarrhythmia. Experimental animal models with sustained rapid pacing can produce severe biventricular systolic dysfunction. Whipple et al. established the first experimental model for biventricular systolic dysfunction in 1962 (1) and his model has since been used for many further studies on this topic. In the clinical setting, TIC is usually seen in patients with no previous structural heart disease, although it may be responsible for ventricular dysfunction aggravation in those with underlying heart disease (2). Data from several studies and from case reports have shown that rate control by cardioversion, negative chronotropic agents, catheter ablation or antitachycardia pacing results in improvement of the ventricular systolic function.

I - Pathophysiology

The normal heart rate in humans is between 55 and 95 beats per minute (3). The sustained heart rate limit above which TIC will appear is not well established. However, a prolonged heart rate above 100 beats per minute may be relevant (4) and deserves attention. TIC may manifest months to years after the onset of the responsible tachycardia, but because TIC is a rate dependent cardiomyopathy, those patients with higher tachycardia rates develop TIC earlier (5,6). Time to onset of ventricular dysfunction is also dependent on the presence of an underlying structural heart disease. Other factors include the type and duration of tachyarrhythmia, the patient’s age, drugs, and coexisting medical conditions (7).

High ventricular rates initially result in cardiac dilatation and mitral regurgitation, which are typically associated with elevated ventricular filling pressures, decreased contractility, right and left ventricular wall thinning, and, eventually, heart failure with neurohormonal activation. Cardiac output is usually reduced, and systemic vascular resistances are typically elevated (8). In experimental models, some of these changes can be seen as early as 24-48 hours after rapid cardiac pacing with continuing deterioration in ventricular function for up to 3-5 weeks.

Abnormal calcium handling, reduced cellular energy storing, and abnormal energy use have been proposed as the underlying mechanisms responsible for this syndrome. These mechanisms determine myocardial remodeling. Cellular changes include loss of myocytes, cellular elongation, myofibril misalignment, and loss of sarcomere register, which may be due to derangement of the extracellular matrix (9).

Table 1 : Described arrhythmias associated with tachycardiomyopathy

- Supraventricular causes

Atrial tachycardia

Atrial flutter

Atrual fibrillation

Atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia

Atrioventricular tachycardia

Permanent junctional reciprocating tachycardia

Atrial pacing at high rates

- Ventricular causes

Premature ventricular complexes

Right ventricular outflow tachycardia (VT)

Idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia

Bundle-branch reentry VT

Ventricular pacing at high rates

II - Clinical features and diagnosis

TIC may present itself at any age and has been reported as a result of various tachyarrhythmia mechanisms (TABLE I [10-14]). Supraventricular tachycardias are more frequently involved than ventricular arrhythmias (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Incessant supraventricular tachycardia due to atrioventricular reentry by a concealed accessory pathway in a young male. The tachycardia is terminated following adenosine infusion but with almost immediate spontaneous reinitiation

However, more recently TIC has also been described as a result of frequent ventricular ectopic beats. This has been explained by the asynergic and inefficient left ventricular contraction of the ectopic beats, which is similar to that reported in patients with left bundle branch block or right ventricular pacing. The resulting abnormal left ventricular torsion may cause disruption and further progression of asynergic left ventricular wall motion.

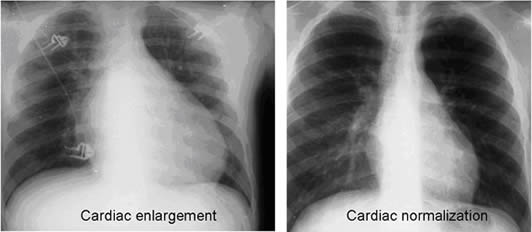

The diagnosis of TIC requires awareness about this condition, as the underlying arrhythmia may not always be apparent. It should be suspected in patients with structural heart disease and heart failure who suffer from chronic or frequently recurring tachyarrhythmias and in all patients with no other obvious explanation for ventricular dysfunction. The diagnosis of TIC in this latter setting can be only confirmed after cardiac function restoration following tachycardia or heart rate control (fig. 2). (15,16).

Figure 2. Chest xray images of the same patient of figure 1 wich were taken on admission (left panel) and 3 months after (right panel) successful ablation of the accessory pathway. Significant resolution of cardiomegaly is apparent.

III- Treatment

Heart rate normalisation, either with rate or rhythm control, is the cornerstone of therapy in TIC. Most of the data available come from patients with atrial fibrillation. In this setting, normalisation of heart rate using any of the two methods (rate or rhythm control) improves systolic function. However, in other clinical scenarios, TIC treatment should be directed to termination of the responsible arrhythmia and to treating heart failure. This approach may include antiarrhythmic drug therapy and DC cardioversion, although, due to the serious potential consequences of this syndrome, a definitive cure to the arrhythmia as can be obtained with a catheter ablation, should be pursued whenever possible (17). Atrioventricular junction conduction ablation followed by pacemaker implantation is also an option for those patients in whom a definitive cure cannot be obtained by other means. However, it has recently been suggested that even heart rate control using this latter approach is inferior in terms of left ventricular ejection fraction recovery to catheter ablation of the arrhythmia substrate (fig. 3) (18) .

Figure 3. Ejection fraction improvement following pulmonary vein isolation and AV nodal ablation in patients with heart failure. (18)

IV - Prognosis

Ventricular dysfunction recovery in TIC patients following sinus rhythm restoration is variable. It depends on the rate and duration of the responsible arrhythmia. Both experimental models and some reports in humans (18-21), showed the greatest left ventricular ejection fraction recovery 1 month after arrhythmia cessation and a more gradual recovery reaching a complete normalisation up to one year thereafter, in some cases. Nevertheless, the impact of recurrent or new tachyarrhythmias on left ventricular function has been poorly assessed. This has been studied in a group of patients with TIC who were followed for 12 years (22) and those who had recurrent tachycardia had a rapidly declining left ventricular function, heart failure, and a high incidence of sudden cardiac death.

Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy is a reversible cause of heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy should be considered in all patients with a dilated cardiomyopathy of uncertain origin and who have tachycardias or atrial fibrillation with a fast ventricular rate. Abolishing tachycardia with drugs or catheter ablation often results in clinical improvement and ventricular function recovery.

Q and A

16 Jan. 2009 :

Question

Dr. Savaş Celebi

Ankara-Türkiye :

How can we discriminate tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy from those secondary tachycardias just following cardiomyopathy? For example TIC after atrial fibrillation vs atrial fibrillation due to cardiomyopathy?

Answer

Prof. Jose L. Merino

You can suspect TIC (or a component of TIC in a patient already with ventricular dysfunction due to other causes) when the patient presents with an almost incessant heart rate above 130 bpm and there is no apparent cause (infection, shock, etc) for it. Nevertheless, sometimes distinction between TIC and other causes of ventricular dysfunction can be very tricky and only possible after HR control.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.