Background

Typical atrial flutter cases (AFL-I) make up 22% of all 8,546 ablation procedures in the Spanish National Ablation's Registry (behind atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, accessory pathways but ahead of atrial fibrillation).

Furthermore, atrial flutter is considered to hold as much risk as atrial fibrillation for thromboembolic events (3-4% per year).(2,3) Atrial flutter also carries a proarrhythmic risk, and additionally, rhythm control and ventricular rate response can only hardly be achieved with medical treatment. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with concomitant bronchodilators especially, controlling the ventricular rate could be challenging with an increased risk of 1:1 ventricular response. Loss of atrioventricular synchronisation and physiological rate response to activity can also decrease functional class in patients with ventricular dysfunction.

We present a brief report describing common atrial flutter as well as the main atypical forms, with a focus on description of their circuits, and main electrocardiographic patterns. (4)

Typical atrial flutter

Typical atrial flutter is an organised atrial tachycardia. It can also be defined as a macroreentrant tachycardia confined to the right atrium. This arrhythmia has a 200-260 ms cycle length, although it may fluctuate depending on patient's previous treatment or ablation, congenital heart disease, etc. (4) Ventricular rate response will be limited by the atrioventricular (AV) node conductions, usually presenting a 2:1 or 3:1 response, during atrial flutter.

Typical atrial flutter originates in a well-known circuit around the tricuspid annulus limited by anatomical barriers such as both the superior and inferior cava veins, the coronary sinus and crista terminalis. The wave front may rotate around this circuit counterclockwise (most frequently) or clockwise, resulting in the counterclockwise common atrial flutter or the clockwise atrial flutter, respectively.(4,5) This condition produces continuous electrical activity around the atrial circuit and consequently in the electrocardiogram (f waves).

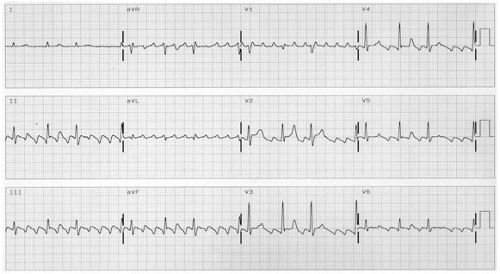

The electrocardiogram shows a saw tooth's pattern in inferior leads, with a slow downward slope followed by a fast upward slope explained by electrical forces going through the cavotricuspid isthmus and the septum, and then approaching the inferior leads through the lateral wall (Figure 1).(4,5) This saw tooth’s appearance could be easily registered when the ventricular rate response is controlled.

Some conditions may make the ECG diagnosis difficult:

- Scarred atria with low areas of voltage could mimic isoelectric baseline despite atrial continuous electrical activity.

- Concomitant circuits could also change the typical atrial appearance.

- Both high and irregular ventricular rate responses may make the diagnosis difficult. In the first case, vagal maneuvers or AV node blocking drugs, such as adenosine, may be useful. In the second case, a regular irregularity has to be always ruled out. (6,7)

Electrophysiological studies (EPs) are indicated:

- In AFL-I recurrences despite medical treatment (Class I indication)

- After the first episode of AFL-I (Class IIa indication), especially in those presenting with poor hemodynamic tolerance or tachymiocardiopathy. (8)

The ablation procedure's main target is to achieve bidirectional block through the cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI). (For a closer look at ablation, see previous e-journal articles on rhythmologist's view on the patient after the procedure, or surgeons' look at procedure in lone atrial fibrillation. See here, previous article on flutter’s differential diagnoses and treatment approaches). Acute success rate is almost 95% in the registries.(1) However, at 5 year follow-up almost 70% of these patients might develop atrial fibrillation or atypical atrial flutter, which is probably related to the baseline characteristics, structural heart disease and uncontrolled risk factors. (9-11)

Main atypical forms

The definition of atypical atrial flutter includes a broad spectrum of other macroreentrant tachycardias in which the wave front does not travel around the tricuspid annulus.

Atypical right atrial flutter other than reverse typical atrial flutter, includes the following: lower loop reentry, fosa ovalis flutter, superior vena cava flutter and upper loop reentry (Figure 2). (12-15)

Lower loop reentry atrial flutter uses a circuit that includes the CTI, as common atrial flutter, but it shortens the circuit through a gap in the crista terminalis. The mean cycle length is usually from 170 to 250 ms. Positive forces in inferior leads and V1 will be underpowered as a consequence of the change in the typical up-down depolarisation of the lateral wall. Upper loop reentry was also described using a circuit through a gap in the crista terminalis and then in the posterior right atrium wall. The electrocardiogram pattern mimics a clockwise typical flutter but the cycle length is usually shorter, as in lower loop reentry. (12,13)

An infrequent form of right atrial atypical flutter is confined within the superior vena cava and from it the atria are passively activated. (14)

A second group could be called incisional flutters which includes those where the circuit uses previous surgery related scars, frequently seen in patients with history of surgical correction of congenital heart diseases. (5,15)

Finally, atypical flutter may originated in the left atrium. In this case, the leading wave front is confined to the left atrium. The most frequent left atrial flutters are perimitral, peripulmonary veins, septal, roof and posterior wall macroreentrys. The surface electrocardiogram usually presents isoelectric baseline or low amplitude and positive regular F waves best in V1 (Figure 3). (13,16)

Eletrophysiological studies are indicated in AFL-II recurrences despite optimised medical treatment. During EPs, the diagnosis and an accurate characterisation of the circuit may be performed by activation and postpacing interval maps, which requires 3D navigation systems. (17,18)

The acute ablation success is inferior to common atrial flutter ablation, probably due to multifactorial issues such as worse clinical baseline characteristics, multiple concomitants atypical atrial flutters, and the instability of the clinical flutter during the procedure. (19,20)

Figure 1. Typical electrocardiographic pattern of common atrial flutter

Figure 2. Right atypical atrial flutter's circuits. SVC: superior vena cava; IVC: inferior vena cava; CT: crista terminalis; FO: Foramen ovale.

Figure 3. Electrocardiographic recording of perimitral atrial flutter. Atrial fluter waves are registered in V1 lead (red arrows).

Conclusion:

Although atypical atrial flutter is characterised by a wavefront not travelling around the tricuspid annulus, it can take on many forms.

Similarly, in typical atrial flutter, cycle arrhythmia, scarred atria, concomitant circuits, high and irregular ventricular rate responses can render diagnosis difficult.

Better knowledge of the underlying mechanisms will probably help to increase accurate diagnoses of common atrial flutter as well as the main atypical forms by cardiologists and emergency department physicians.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.