How to measure the QT interval?

Diagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS) is based on either a prolonged rate corrected QT interval (QTc) on repetitive ECG’s in the absence of QT prolonging drugs or ion disturbances, a Schwartz score ≥3.5 or presence of a pathogenic variant in a LQTS causing gene.1 Measuring QTc might sound easy, but is in fact a challenging task. It was shown that world-renowned LQTS experts measure the QTc interval in LQTS patients with a variation up to 70 ms.2

Measurement itself

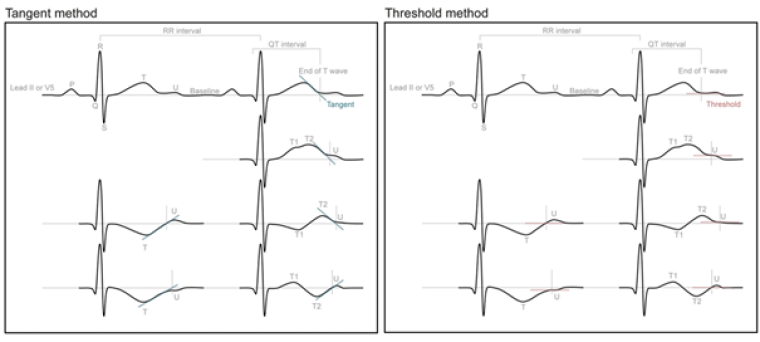

The QT interval is defined as the interval between the onset of QRS and the end of the T wave. Manual measurement of the QT interval is advised over automated measurement, as these automatic assessments struggle with aberrant T wave patterns often observed in LQTS patients resulting in high variation between manual and automated measurement.3 The end of the T wave can be measured by 2 different methods (figure 1).4 The first method is called the tangent method and is defined as the intersection of a tangent to the steepest slope of the last limb of the T wave and the isoelectric baseline, defined as the voltage at QRS onset. The second method is called the threshold method and is defined as the intersection of the terminal limb of the T wave with the isoelectric baseline. The tangent method usually results in a 10ms shortening of QTc compared to the threshold method.4 LQTS patients often show pronounced T wave morphology abnormalities complicating the measurement. Biphasic T waves should be included in the measurement, while U waves should be excluded. Measurements are preferentially done in lead II or V5.

Because there is no gold standard against which these 2 measurement methods can be compared with, it remains uncertain which method is preferable. It has been shown that the Tangent method is easy to learn and is therefore likely to be more reproducible between different physicians.5 However, it could miss the last part of repolarization leading to an underestimation of the QTc. Therefore, among experts there is still no consensus on which should be the preferred method.

Correction for heart rate

Since the QT interval changes with heart rate, it is common practice to correct the QT interval to the value you expect for a heart rate of 60 BPM. Correction for heart rate is usually done by generalized formula, of which Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT/√(RR)) is the most commonly used and validated in LQTS. Nevertheless many shortcomings of Bazett’s formula like overcorrection at high heart rates and undercorrection at lower heart rates are well known.6 Other generalized formulae have been proposed including Fridericia’s formula (QTcFri=QT/RR1/3) and Rautaharju’s formula that is validated in patients with prolonged QRS duration. As the QT heart rate dependence is very individual, especially in LQTS patients, individualized QT interval (QTi) based on the patient’s own QT-RR behavior measured on 24 hour holter recordings has been proposed as an alternative method.7

Normal values

There is substantial overlap in QTc between patients with LQTS and healthy individuals.8 However LQTS patients with normal QTc solely diagnosed on the basis of a positive genetic test are important to identify as these so called concealed LQTS patients have an augmented risk of sudden death (4% between birth and age 40) compared to genotype negative control individuals.1

The cut-off to define prolonged QTc has been shifted over the years and according the latest ESC guidelines a gender independent Bazett corrected QTc ≥ 480 ms or QTc ≥ 460 ms in a symptomatic individual is diagnostic.1 Age, gender and measurement method are important modifiers of the QTc, but are not incorporated in these guidelines.

Based on the QTc of over 800 genotype confirmed LQTS patients and almost 600 genotype negative family members a QT calculator to calculate the probability of LQTS incorporating gender, age and different methods to define the end of the T wave was proposed by the Amsterdam group (https://www.qtcalculator.org/)

Conclusion

QT measurement at this point in time should be done manually using either the tangent or threshold method in lead II or V5, using Bazett’s formula to correct for heart rate. QTc above 480ms is diagnostic, however different cut-offs are proposed by different experts. If you want to read more on congenital LQTS, a detailed overview by several world-renowned LQTS experts was recently published.9

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.