Background

In the recently published ESC guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies [1], the task force introduced several new concepts and recommendations, among which was a new phenotype-based description for cardiomyopathies. Included in this is a new definition of non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy (NDLVC), defined as the presence of non-ischaemic left ventricular (LV) scarring or fatty replacement regardless of the presence of global or regional wall motion abnormalities (RWMAs), or isolated global LV hypokinesia without scarring. This phenotype encompasses a group of patients that may previously have been variably characterised as hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy [2], dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) (but without the presence of a dilated LV); or arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy (ALVC), left-dominant ARVC, or arrhythmogenic DCM (but without fulfilling diagnostic criteria for ARVC). Here we present a pediatric patient with initial features of NDLVC, evolving phenotypically towards DCM, and demonstrating the importance of following the ‘patient pathway’, as highlighted in the recently published guidelines.

Case Presentation

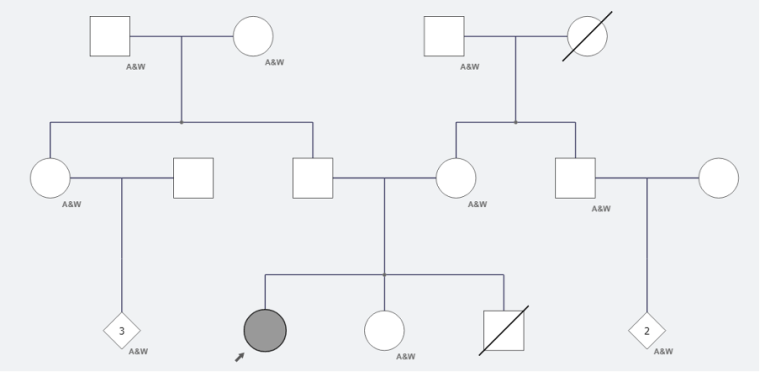

A previously fit and well 14-year-old girl presented to urgent care with a brief episode of syncope on a background of ongoing nausea and vomiting. This was in the context of her menstrual cycle, with known menorrhagia, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting but no prior syncope. Due to her menorrhagia, she had been commenced by her primary care physician on a progesterone-only oral contraceptive pill, desorgestel. There was no relevant cardiac family history, and no family history of sudden death. There was a previous stillbirth at 28 weeks, as demonstrated in figure 1. There was no clear history of previous infection.

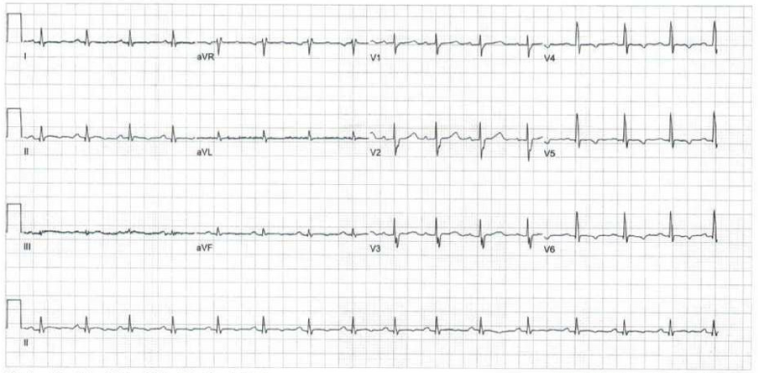

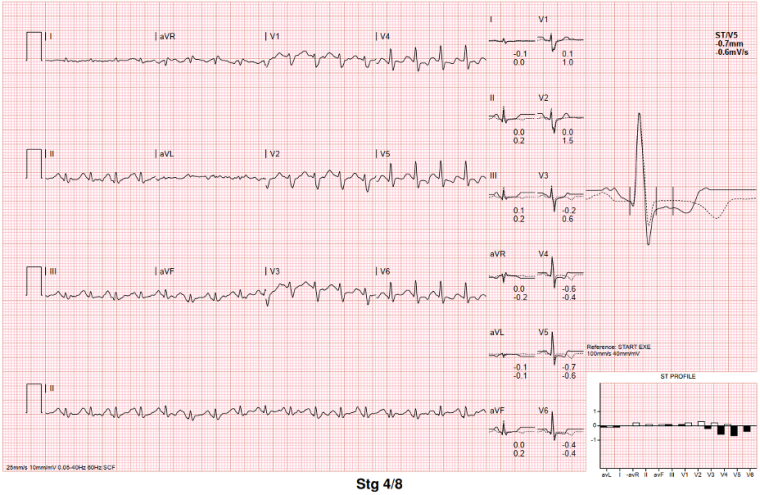

In the emergency department, a physical examination was undertaken, which was unremarkable, and given the episode of syncope, an ECG was performed (figure 2):

Figure 2: Baseline ECG demonstrating sinus rhythm (HR 93bpm), normal axis (+34o), PR interval 146ms, intraventricular conduction delay (QRS duration 86ms), delayed R wave progression, repolarisation abnormalities (T wave inversion laterally, flat inferiorly), and a normal QT duration (QTc 438ms).

The baseline ECG as presented above prompted referral to a paediatric cardiologist, who 3 months later repeated an ECG and performed a baseline echocardiogram. This revealed borderline normal left ventricular (LV) size (LVEDD 51mm, z-1.7 LVESD 41mm, z+2.1), with slight thinning of the LV walls, moderate LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF by biplane 40%). The valvular appearances, coronary arteries and the right ventricular size and function were normal. The patient was commenced on lisinopril due to her systolic dysfunction.

A contrast-enhanced cardiac MRI was performed one month later, which confirmed the presence of mild LV dilatation (LVEDV 181.7mL, z+2.9) with reduced systolic function (LVEF 45%), with no focal thinning or hypertrophy. There were linear mid septal streaks of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) with some patchy epicardial areas of LGE. RV volumes were normal with preserved global systolic function. On this basis, a diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy was given to the patient.

A concurrent 24-hour Holter monitor showed frequent monomorphic ventricular ectopy (VE) (burden 1%), with no evidence of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT).

She underwent genetic testing in September 2022, which identified a pathogenic truncating variant in the desmoplakin (DSP) gene (Arg160*), in heterozygosity.

From a symptomatic perspective, having previously been entirely asymptomatic, since her diagnosis the patient reported symptoms of dyspnoea on relatively modest exertion, and she was therefore commenced gradually on bisoprolol, spironolactone, with the latest addition of sacubitril-valsartan. The addition of sacubitril-valsartan improved her symptoms, but she remained in NYHA functional class II. Her Troponin I and NT-pro-BNP were persistently elevated. Her ongoing symptoms prompted a referral to a tertiary pediatric inherited cardiovascular conditions (ICC) service in one year following her initial presentation. With the support of a highly specialised multidisciplinary team (MDT), including a specialised advanced nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, a genetic counsellor in ICC and a psychology team, the consideration of implantation of a primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was put to the family.

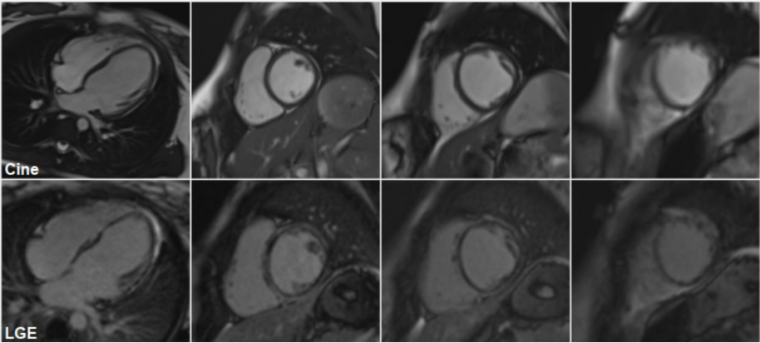

A repeat cardiac MRI was performed on March 2023 (figure 3):

Figure 3: Cine (top) cardiac MRI frames, demonstrating a mildly dilated LV cavity, with thinning of the apical segments and LGE (bottom) cMRI frames showing an almost circumferential ring-like appearance of gadolinium enhancement at the base mid cavity, extending apically.

This confirmed the presence of left ventricular dilatation (LVEDV 101 mL/m2, z+2.6; LVESV 57 mL/m2, z+6.4) with reduced global systolic function (LVEF 43%). There was thinning of the apical segments and regional wall motion abnormalities, affecting in particular the mid cavity to apical septum and the apical anterior wall. The left atrium was not dilated. There was extensive subepicardial and mid wall LGE in a nonischaemic pattern, involving the inferior, lateral, anterior wall and septum with an almost circumferential ring-like appearance at the base mid cavity, extending to the apical segments. RV volumes were again normal with preserved global systolic function.

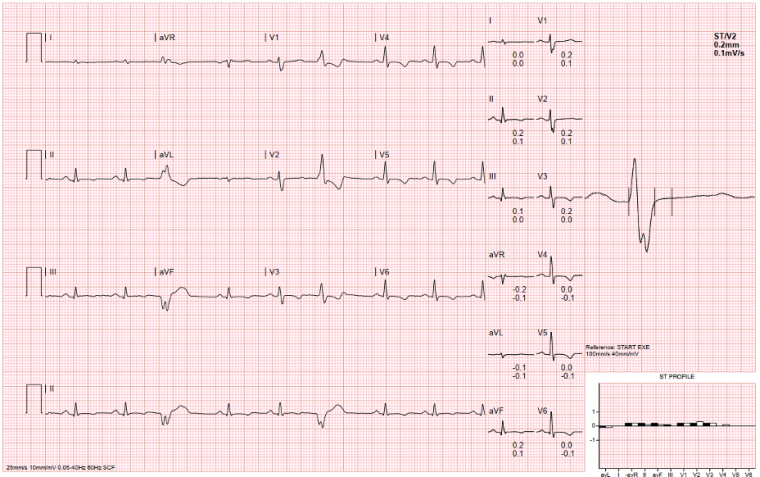

On exercise testing (figure 4), there were isolated ventricular ectopics of at least 2 different morphologies at rest and during early exercise, in isolation and in a trigeminal pattern, longest for 5 cycles, of one morphology. She developed symptoms of breathlessness at stage IV of the exercise test but no syncope or presyncope. There were non-specific ST segment changes throughout.

Figure 4: ECG during exercise test, demonstrating ventricular ectopics during rest (top), suppressing during peak exercise (bottom), with persistent non-specific ST segment changes.

A repeat 24-hour Holter in March 2023 showed a 5-beat run NSVT at a rate of just over 120 bpm (figure 5).

Figure 5: Short strip from 24-hour Holter monitor demonstrating 5-beat NSVT (HR 126bpm)

This strengthened the recommendation for the implantation of a primary prevention ICD, which, with the support of the MDT, the family agreed to.

The patient was implanted with an endocardial ICD, after failing the screening for a subcutaneous system, in August 2023. Clinically, she remains very stable, with no recent episodes of syncope, presyncope, chest pain or palpitation. She still describes NYHA functional class II symptoms, becoming breathless after climbing a few flights of stairs. There is no history of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea or orthopnoea. She remains on the same medication protocol (bisoprolol, spironolactone and Entresto, as well as aspirin and desorgestel).

Family screening of first-degree relatives has been recommended.

Discussion

We present a case of a teenage girl, presenting with NDLVC progressing to a DCM phenotype, secondary to a truncating DSP variant, with no relevant prior family history, persistent heart failure related symptoms needing therapy and a high risk for malignant arrhythmias, prompting primary prevention ICD implantation. This case, although demonstrating a typical picture of a truncating DSP variant, is interesting as it demonstrates several important points.

This patient presented to a local pediatric emergency department with a primary complaint of continued vomiting. Through a thorough history of presenting complaint, the clinicians identified the brief episode of syncope, and although it was likely vasovagal in nature, they elected to perform an ECG. They subsequently identified the repolarisation abnormalities and appropriately referred the patient to a cardiologist. This highlights the importance of the ‘patient pathway’, as at times, the clinical presentation may be inconspicuous, and at a young age, and so thorough baseline investigations at a primary and secondary care setting with a “cardiomyopathy mindset” are crucial, as is the ability to correctly identify ‘red-flag’ signs, such as lateral repolarisation abnormalities on baseline ECG, to prompt secondary investigations.

The importance of thorough secondary investigations is also stressed with this case. The pediatric cardiologist that reviewed this patient, performed all the relevant baseline cardiac investigations, including 24-hour Holter monitor and a cardiac MRI, which is now a class I recommendation at the initial evaluation of cardiomyopathies, guiding both diagnosis and prognosis. Importantly, and despite the lack of family history, genetic testing was performed, another class I recommendation, which greatly aided in the diagnosis and management of the patient, with continuous assessment and titration of medication.

As discussed in the guidelines [1], a stepwise approach is needed, with a careful analysis of multiple investigations and parameters in order to characterise the morphological and functional traits of the condition and generate a phenotype-based aetiological diagnosis, followed by a molecular diagnosis, so as to provide disease-specific management. A truncating variant in NMD competent regions of the gene are known to cause haploinsufficiency and are linked to a younger age at diagnosis and an increased risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias compared to variants in NMD incompetent regions [3]. Therefore, it is crucial, such as in this case, to perform genetic testing early and identify any potential disease-causing gene variants [4], to correctly risk-stratify each patient and offer appropriate therapies. In the case of DSP variants, the annual SCD incidence is estimated at 3-5% [1, 3].

We also demonstrate the significance of continued monitoring and risk-assessment, as this patient’s phenotype evolved, in a short time-period, despite her young age. At her very first appointment in her local cardiology unit, her LV was non-dilated, and with the presence of a reduced systolic function, would fit the current diagnosis of NDLVC. However, on serial assessment, the LV size increased, becoming more of a dilated phenotype, with reduced systolic function. While the initial MRI did not demonstrate any specific LGE pattern, a repeat cardiac MRI identified the presence of LGE in a ring-like pattern, characteristic of DSP gene variants [5], and a repeat cardiac monitor confirmed the presence of NSVT. In this case, the genotype, reduced LVEF and the presence of NSVT on cardiac monitoring and LGE on CMR all increased the patient’s risk of SCD [1, 5,6], prompting discussions around an ICD.

As highlighted in the recent ESC guidelines [1], this case is an example of the importance of a multi-disciplinary approach in the care of ICC patients, as well as a patient-centred approach. With the use of a genetic counsellor to discuss implications of genetic testing and results, a specialised nursing team to answer patient and family concerns as well as a psychology team to discuss the variety of aspects of a teenager’s and their family’s everyday life affected by this diagnosis and interventions, had led to a shared decision-making process between the patient, her family and healthcare professionals. The involvement of a genetic counsellor and psychologist are stressed in the guidelines as class I recommendations.

Conclusion

With this case of a teenager, with initial findings consistent with NDLVC, progressing into DCM, secondary to a truncating DSP variant, we demonstrate the importance of the cardiomyopathy mindset, prompting thorough investigations, accurately characterising the patient’s phenotype to allow for appropriate testing, including genetic testing, in order to risk-stratify and offer phenotype-specific management. Furthermore, we highlight the significance of a shared decision-making process with the aid of a multi-disciplinary team, patient-centred approach.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.