Take-home messages

- Obesity is and should be managed as a chronic disease, as early as childhood.

- The role of the Cardiologist is essential, as obesity is linked with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

- Diet, physical activity, and psychological interventions are the fundamental basis of its management.

- Prolonged efforts are required to achieve lifelong adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviours and ensure the beneficial long-term effects of associated drugs.

Definition, epidemiology and diagnosis

Obesity, defined by excessive fat deposit, is associated with adverse health outcomes and reduced life expectancy and requires long-term intervention. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared obesity a disease in 1997 and the European Commission followed suit in 2021 [2]. Obesity is one of the most serious global public health problems. From 1990 to 2015, obesity accounted for >4.0 million deaths, two-thirds of attributable to cardiovascular disease [3]. Body mass index (BMI) is a surrogate marker of fat-related risk and largely used to classify obesity (Table 1).

Table 1. World Health Organization classification of overweight and obesity in adults. With permission from [1].

|

BMI = Weight (Kg) Height2 (m2) |

|

|

Normal weight |

|

Overweight |

|

Obesity |

| BMI 30 to <35 kg/m2: |

Obesity Class 1 |

| BMI 35 to <40 kg/m2: |

Obesity Class 2 |

| BMI ≥40 kg/m2: |

Obesity Class 3 (severe) |

Generally, obesity is caused by an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure. Genetic and biological factors influence individual development of obesity, but the worldwide obesity epidemic is largely driven by environmental/socio-economic factors [1].

Although the prevalence of obesity increases markedly in the third to fifth decade of life [1, 4], childhood obesity is expected to increase substantially, and is linked with cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality in adulthood. Thus, it is important to reduce CV risk as early as childhood, physical inactivity and unhealthy diet being key determinants [1,5].

BMI provides the most useful population-level measure of obesity, but individuals with similar BMI may have different cardiometabolic risk [1,6]. Other measurements, including waist circumference, waist-to-hip or waist-to-height ratios may better predict CV risk [7-9]. In practice, the lowest all-cause mortality is observed in those of both sexes with a BMI of 20–25 kg/m2, and, concerning waist circumference, the ESC Prevention Guidelines advise weight reduction for men with a waist circumference >102 cm and >88 cm in women [10].

Finally, obesity induces pericardial, epicardial, and perivascular adipose tissue and the total fat content surrounding the heart has been associated with prevalent cardiovascular disease (CVD), independent of obesity metrics [11]. Notably, epicardial fat has been correlated with subclinical atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease (CAD) and its evaluation holds promise for cardiometabolic risk stratification in the future [12]. While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) can both assess visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue, CT is the gold standard for their volumetric assessment.

A review of ESC Guidelines for the management of CV risk

In patients with Type 2 diabete mellitus (T2DM), it is recommended that individuals who are overweight or obese aim to reduce their weight and increase their physical exercise to improve both metabolic control and their overall CVD risk profile (Class I, Level of Evidence [LoE] A) [13,14].

In hypertensive patients, it is recommended to aim for a stable and healthy BMI (20–25 kg/m2) and waist circumference values (<94 cm in men and <80 cm in women) to reduce blood pressure and CVD risk (Class I, LoE A) [15].

Blood pressure-lowering drug treatment is recommended for people with pre-diabetes or obesity when their confirmed office blood pressure is ≥140/90 mmHg, or when office blood pressure is 130–139/80–89 mmHg and the patient is at predicted 10-year risk of CVD ≥10%, or with high-risk conditions, despite a maximum of three months of lifestyle therapy (Class I, LoE A) [15].

In the Look AHEAD trial, overweight or obese patients with T2DM who received intensive lifestyle intervention (reduced caloric intake and increased physical activity), a loss of 5−10% body weight was associated with a 56% and 48% greater likelihood of achieving a 5 mmHg decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively. Greater weight loss was associated with larger blood pressure reductions [16].

Concerning lipid measurements, if available, Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) analysis is recommended for risk assessment in people with obesity as an alternative to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) as the primary measurement for screening, diagnosis, and management of dyslipidaemia (Class I, LoE C) [17].

For dyslipidaemic patients, a meta-analysis of 73 randomised controlled trials found that weight loss decreased triglycerides (5-10% weight loss can decrease triglyceride levels by 20%) and LDL-C, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [18].

In patients with obesity, regular screening for non-restorative sleep is indicated (e.g., by the question: ‘how often have you been bothered by trouble falling or staying asleep or sleeping too much?’) (Class I, LoE C) [10].

Treatment strategies: lifestyle interventions

Treatment of obesity is based on a combination of dietary, physical activity, and/or psychological interventions, and can be complemented by pharmacotherapy and bariatric procedures. It requires prolonged and laborious efforts by motivated individuals to achieve lifelong adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviours. Providing tailored, individualised guidance is crucial. In patients with a catabolic dominance (advanced heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cancer), nutritional restrictions should be avoided or done with great caution.

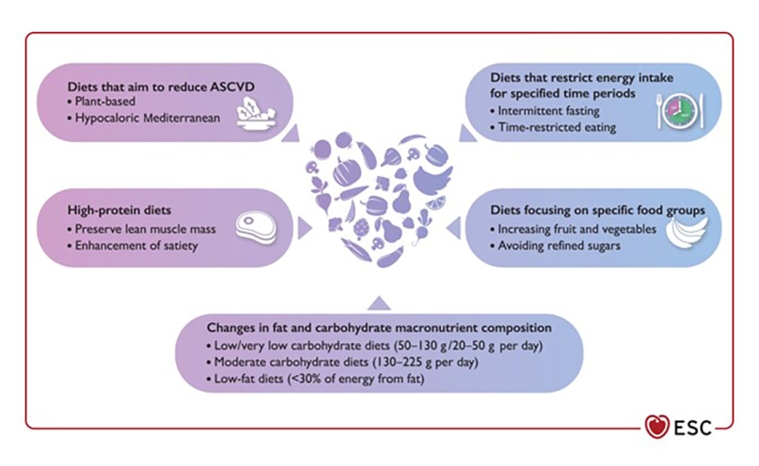

In general, dietary interventions aim for reduced caloric intake with a 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit that can be adjusted for individual body weight and activity [19]. Numerous strategies exist to reduce caloric intake including portion size control, a reduction or elimination of ultra-processed foods and alcohol consumption, and increased fruit and vegetable intake. Various nutritional approaches (low fat-vegan, vegetarian style, low carbohydrate, and Mediterranean diets) have been proposed [19], as shown in Figure 1. Most dietary patterns resulted in broadly similar, modest (5%-10%), short-term (6 months) weight loss, and only the benefits of the Mediterranean diet tended to persist at later follow-up (12 months) [20].

Figure 1. Overview of most common hypocaloric diet patterns for weight loss. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Reproduced with permission from [1].

Physical activity (*) has the potential to shift fat mass to muscle mass and modify fat distribution [1]. Although average effects on weight loss are modest, exercise is prescribed for the treatment of CV risk, with the potential to enhance mental health and improve CV outcomes.

Whether a person benefits from endurance or strength/resistance training depends on individual factors [21], and the protocol choice should be tailored to the individual.

In the current ESC guidelines, the common recommendation for the general adult population is at least 150–300 min per week of moderate or at least 75–150 min per week of vigorous physical activity to reduce all-cause mortality, CV mortality, and morbidity [10], with further recommendations for additional strength exercises two to three times a week [22]. Importantly, individuals who cannot achieve the aforementioned exercise goals should be advised to stay as active as their abilities allow and encouraged to switch to non-sedentary behaviours throughout the day, such as walking for 2 min each hour or the use of stairs [23].

(*) linked to video/podcast with Prof H.Hanssen from this issue.

Psychological interventions

Obesity is stigmatised in the public, and often associated with negative attitudes and discrimination [24]. A supportive environment can be facilitated firstly using examination tables and chairs that accommodate all body sizes. A supportive, non-judgmental approach is essential. Evidence-based counselling strategies, as the 5As (Assess, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) can help establish a positive relation and guide shared decision-making [1,25,26].

Multicomponent behavioural interventions represent an important tool in obesity management and several evidence-based commercial multimodal programmes are available [19,22,26,27]. They typically include 12 or more sessions in the first year, followed by a maintenance phase for ∼24 months [22]. They may consist in group, individual, or technology-based delivery for lifestyle changes, education, peer support, self-weighing, coaching, self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, and goal setting [27].

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.