Take-home messages regarding the medication for obesity [1]

- Currently, semaglutide 2.4 mg administered weekly is the only weight loss intervention with demonstrated beneficial outcomes in patients with established CVD without type 2 diabetes mellitus.

- Orlistat and the combination of bupropion/naltrexone should be prescribed cautiously as especially in patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD), due to their modest impact on body weight, limited evidence on cardiovascular safety, and concerns about potential long-term cardiovascular risks.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have demonstrated effectiveness in promoting weight loss and improving cardiovascular risk factors.

- The effects of treatment are largely contingent upon the duration of administration. More research is needed to understand the long-term effects and the maintenance of efficacy of weight loss medications.

Introduction

Changing lifestyle habits is fundamental to managing obesity. However, if lifestyle interventions do not lead to adequate weight loss, the next step is to start an anti-obesity medication as these have been demonstrated to lower cardiometabolic risk in individuals with obesity. These medications are generally recommended alongside lifestyle changes for individuals with a BMI of 30 kg/m² or higher, or a BMI of 27 kg/m² or higher with at least one weight-related health condition [1].

In general, weight loss of 5% to 10% or more is recommended to effectively reduce the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic complications associated with obesity [2,3].

GLP-1 receptor agonists: semaglutide and liraglutide

The STEP 5 program examined the impact of subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg administered once weekly compared to a placebo on weight loss in individuals with obesity, who had a mean baseline BMI of 38.6 kg/m² [4]. In the STEP 1 trial, combined with lifestyle counselling, semaglutide 2.4 mg resulted in a 12.4% greater body weight loss than the placebo after 68 weeks [5]. Furthermore, 32% of participants on semaglutide achieved weight loss of 20% or more, a milestone previously attainable only through bariatric surgery. This weight loss was associated with positive changes in systolic blood pressure and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. While no additional weight loss occurred after 60 weeks of treatment, those who continued the medication maintained their weight loss for over two years [4].

The analysis of body composition via DEXA scan showed that 39% of the weight lost in patients treated with semaglutide was lean body mass, while 61% was fat mass. Regarding cardiovascular outcomes, in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and high cardiovascular risk, semaglutide at doses of 0.5 or 1.0 mg once weekly (not the 2.4 mg used for obesity treatment) resulted in a 26% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared to placebo in a non-inferiority trial [6].

The SELECT trial [7] is the first dedicated randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the effects of semaglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with existing cardiovascular disease (CVD) who are overweight or obese (BMI ≥27 kg/m²) but do not have diabetes.

Among the 17,604 participants, 82.1% were found to have known coronary artery disease (CAD) at baseline, with 76.3% having a history of myocardial infarction, and 24.3% experienced chronic heart failure, with 12.9% having heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Over a mean follow-up period of 40 months, semaglutide 2.4 mg administered once weekly was superior to placebo in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke. Patients treated with semaglutide lost an average of 9.4% of their body weight during the first two years, compared to just 0.88% with the placebo group. Additionally, semaglutide resulted in significant reductions in systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), LDL-C, and triglycerides. In a direct comparison, semaglutide 2.4 mg proved more effective in reducing body weight than liraglutide 3 mg taken once daily in individuals with overweight and obesity without diabetes [8], achieving a mean difference in weight loss of 9.4% over 68 weeks. Oral semaglutide 50 mg daily is currently tested (not yet approved by the European medicines agency [EMA]). The first results are promising and showed a body weight change of 12.7% at 68 weeks in patients with high CV risk, who are overweight (BMI ≥27 kg/m²) or obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) without diabetes [9].

Naltrexone/bupropion

Bupropion, a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, and naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist, work together to enhance the central release of proopiomelanocortin, resulting in altered decreased appetite and increased feelings of fullness.

In the largest randomised trial, the COR-II trial, patients treated with 32/360 mg dose experienced a placebo-adjusted weight loss of 5.2% after one year, with 50.5% of individuals achieving a weight loss of 5% or more compared to 17.1% in the placebo group [10].

A meta-analysis of four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) indicated a modest but significant average reduction in baseline body weight of 2.5 kg (range: 1.9-3.2 kg) for those taking naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo [11].

Because of recent safety concerns, prescribing this medication to patients with cardiovascular disease should be approached with caution [12].

Orlistat

Orlistat functions in the intestinal lumen by selectively inhibiting gastric and pancreatic lipases, resulting in reduced dietary fat absorption. The weight loss under this medication is modest compared to placebo but it significantly lowers the risk of developing diabetes [13]. Notably, orlistat has been shown to decrease HbA1c levels in overweight or obese diabetic patients, regardless of any weight loss.

There are no cardiovascular outcomes trials specifically for orlistat, and patients with cardiovascular disease were excluded from the major clinical trials [1].

Tirzepatide

Tirzepatide operates through a dual mechanism by stimulating the endogenous glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1. Chronic activation of GIP works centrally to enhance feelings of fullness and peripherally to slow gastric emptying and promote the health of white adipose tissue.

In clinical studies, subcutaneous tirzepatide demonstrated greater weight loss and reductions in HbA1c compared to semaglutide 1 mg administered once weekly in diabetic patients [14]; however, it has not yet been evaluated against semaglutide 2.4 mg. The results from the SURMOUNT-1 trial revealed that tirzepatide doses of 5, 10, and 15 mg led to average body weight loss of 15.0%, 19.5%, and 20.9%, respectively, over 72 weeks, compared to just 3.1% with placebo in overweight or obese non-diabetic patients [15]. Tirzepatide was associated with a higher rate of reversal from prediabetes to normoglycaemia compared to placebo. A post hoc pooled analysis of the SURPASS trials indicated that the enhancement in glycaemic control in diabetic patients is influenced only in part by weight loss mechanisms [16].

The SURMOUNT-MMO trial is currently in progress, assessing the impact of tirzepatide on cardiovascular outcomes in non-diabetic obese patients (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05556512).

ESC Guidelines recommendations on GLP-1RAs

- Glucose-lowering medications with effects on weight loss (e.g., GLP-1 RAs) should be considered in overweight or obese patients with T2DM to reduce weight (Class IIa, Level of Evidence [LoE] B).

- GLP-1 RAs with proven CV benefit (liraglutide, semaglutide s.c., dulaglutide, efpeglenatide) are recommended in patients with T2DM and atherosclerotic CVD to reduce CV events, independent of baseline or target HbA1c and independent of concomitant glucose-lowering medication (Class I, LoE A) [17].

- The GLP-1 RA semaglutide should be considered in overweight (BMI >27 kg/m²) or obese chronic coronary syndrome patients without diabetes to reduce CV mortality, MI, or stroke. (Class IIa, LoE B) [18].

Intragastric and surgical interventions

Among different endoscopic intragastric procedures that restrict gastric capacity, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and EMEA have approved only intragastric balloons that require an upper endoscopy. The current recommendations for endoscopic procedures in patients with one or more obesity-related comorbidities include a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m² or higher, as well as a BMI of less than 40 kg/m², or a BMI over 27 kg/m² or BMI >27 kg/m2 in patients with one or more obesity-associated comorbidities. Additionally, the FDA has approved endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty for patients with a BMI ranging from 30 to 50 kg/m² [19].

Bariatric surgery is the most effective weight loss intervention, and it is reserved for strictly selected individuals. There are two main procedures: the first is laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and the second is laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery, in which a small gastric pouch is connected directly to the jejunum [1].

The main indication for bariatric surgery is for patients with a BMI of 40 kg/m² or higher, or those with a BMI of 35 kg/m² or higher who have at least one obesity-related condition [20]. Lower thresholds are applicable to certain Asian populations. The choice of surgical procedure should be determined in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team [20].

In terms of the cardiometabolic risk profile, bariatric surgery has been shown to effectively induce remission of T2DM for approximately 10 years and to achieve histological resolution of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis [1]. A recent meta-analysis of observational studies indicated that bariatric surgery is linked to lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, as well as a decreased incidence of heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke [21]. However, no prospective RCTs exist to assess the effect of bariatric surgery on CV outcomes so more data are needed to confirm the positive results of observational studies.

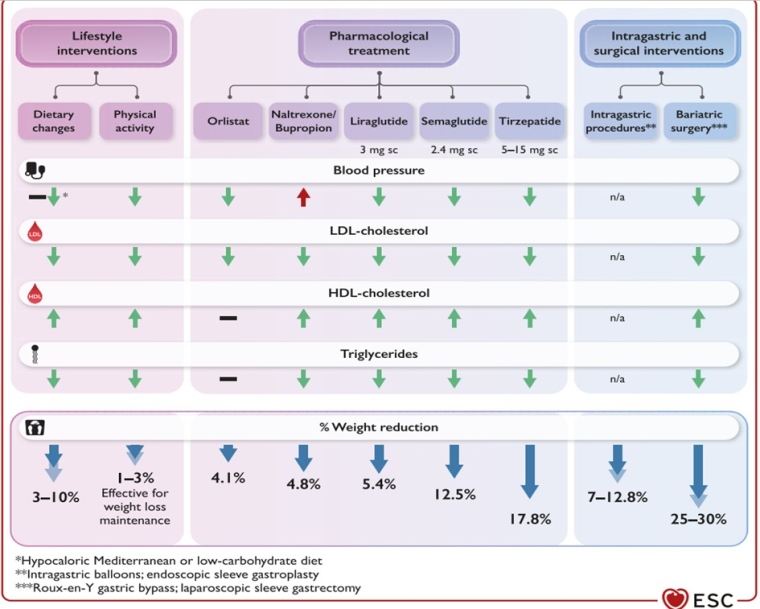

Figure 1. Expected effects of weight loss interventions on cardiovascular risk factors and body weight. Reproduced with permission from [1].

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; n/a, not available

Conclusions

The obesity epidemic requires profound societal changes and multidisciplinary medical interventions and all physicians, particularly cardiologists, must be involved. More emphasis should be placed on primary and secondary prevention and obesity should be managed as a chronic disease. Recent pharmacological agents seem highly promising and combination therapies, in a patient-centred approach should be delivered.

Cardiologists should be involved in anti-obesity programs, proposing new therapies and, when necessary, surgical solutions. However, it should be emphasised that lifestyle interventions are still the essential first step and that drug treatment should be used as a complimentary treatment rather than substitute. With this in mind, life-long adherence to a healthy lifestyle is crucial to maintaining the beneficial long-term effects of these drugs.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.